Matter

Protomatter

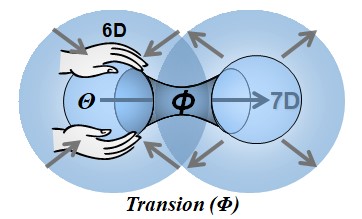

If spacetime unfolds within a six-dimensional hyper-volume, it appears that this is not the ultimate limit of CELA’s extension. When internal pressure becomes too high—exceeding the ability of spations to contain it along the six axes—a confinement rupture may occur.

When the local pressure within a spation exceeds its maximum coherence limit, its internal structure can no longer be maintained in the six-axis configuration that defines ordinary spacetime. In this situation, one of the six axes is replaced by axis 7, giving rise to a seven-axis configuration. This transformation does not displace the spation; it modifies its internal structure. The reconfigured spation no longer belongs to 6D spacetime, because it no longer obeys the connection rules that make spacetime continuous and observable. It therefore becomes invisible from our domain, even though it continues to exist within a more compact and denser 7D structure. This phenomenon is not a gradual transition, but a threshold: as soon as the 6D configuration ceases to be stable, axis 7 is immediately selected.

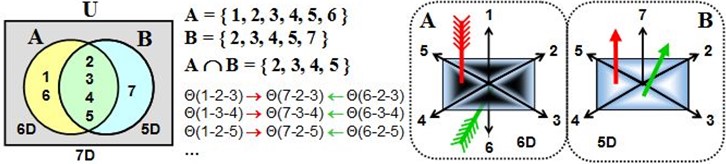

This representation is deliberately simplified. When axis 7 intervenes, the resulting structure is no longer described by the usual combinations of the six spacetime axes. In this new domain, certain additional configurations become possible, but they are not accessible from 6D spacetime. We call this second domain B to distinguish ordinary spacetime (domain A) from the region where axis 7 is active. In this page, we will continue to focus exclusively on phenomena occurring in A.

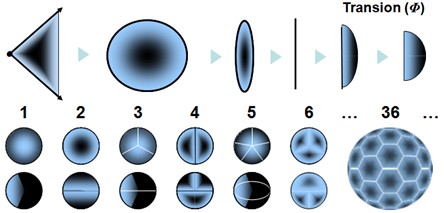

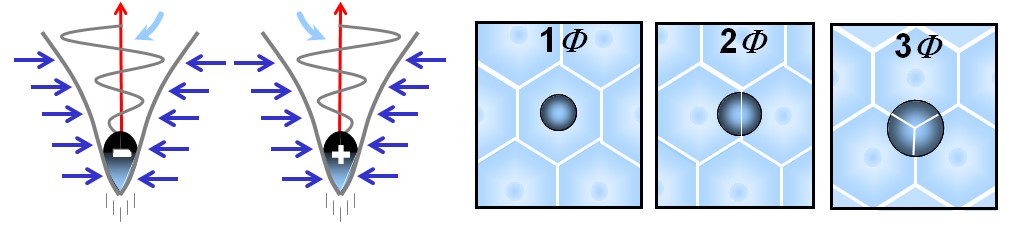

Given the extremely high pressure prevailing in spacetime, when a spation exceeds its coherence limit and switches to a 7D configuration, it immediately ceases to belong to the 6D domain. The precise point at which this switch occurs is called a transion. A transion is not a “hole” and does not yet involve flow or collective displacement. It is simply the point where a spation loses its six-axis structure and adopts the seven-axis structure, thus becoming invisible to the 6D domain. In the illustrations that follow, we represent a transion as a small circle at the center of the diagrams, indicating where this domain change takes place.

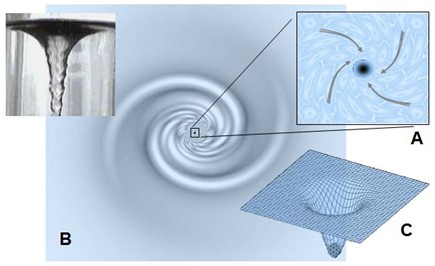

When a transion persists in spacetime, it no longer acts solely on the spation that crossed its limit: it induces an influx of surrounding spations toward its center. Under the effect of the colossal pressure of the medium, neighboring spations are progressively drawn toward the transion.

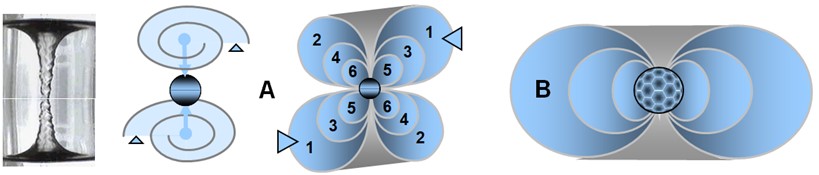

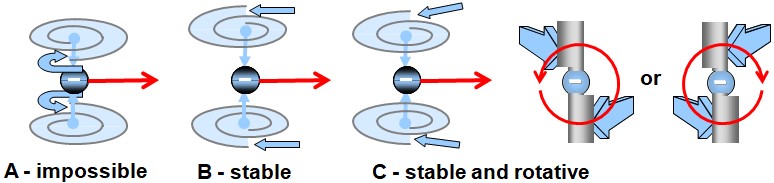

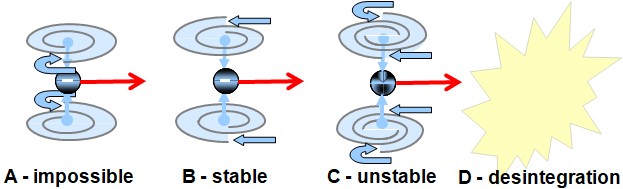

As illustrated in (A), this motion does not occur in a straight line: the viscosity of the spationic field imposes a rotation. The spations therefore begin to spiral around the transion, forming a stable vortex.

Figure (B) provides a classical analogy: that of a vortex in a liquid, visually capturing the dynamics of structured descent. But unlike an ordinary fluid, this vortex does not “fall” toward a material center: the motion follows a dimensional orientation induced by the transion.

In (C), local pressure decreases toward the vortex core. Pressure energy is converted into kinetic energy. This pressure drop reinforces suction, which sustains the spiral flow: the vortex becomes self-feeding.

When a transion simultaneously entrains an even number of spations, the flow splits into two conjugate vortices, as illustrated in (A). These vortices rotate in opposite directions and stabilize one another. This structure remains possible as long as the number of transferred spations remains small. However, when the number of spations entrained simultaneously increases, synchronizing the two vortices becomes increasingly difficult: the slightest pressure fluctuation destabilizes the configuration and tends to make it collapse. In this regime, the configuration spontaneously reorganizes into a single vortex, as illustrated in (B). This unipolar structure then becomes more stable, more coherent, and more probable than the bipolar configuration. This shift in stability will play an essential role in the emergence of charge and particle families, studied in the following image.

Fermion-Type Particles

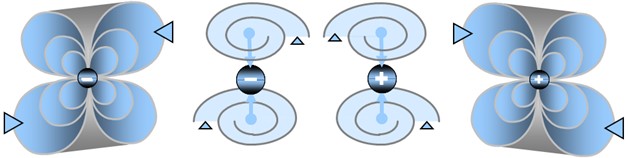

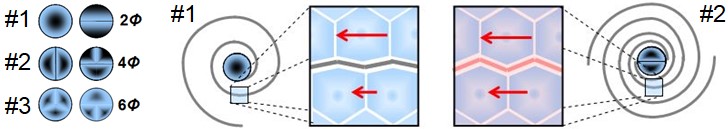

Any fermion-type particle—that is, any particle endowed with stable mass—possesses an internal circulation of the spationic field organized as a vortex. This internal motion is not random: it winds in a spiral. This spiral can rotate in one direction or the other. This is called chirality:

- s = -1: the vortex rotates in one direction

- s = +1: the vortex rotates in the opposite direction

Chirality does not change the shape of the particle, but it determines the sign of its electric charge. In other words, it is not the particle that changes, but the direction of its internal vortex. Thus, a particle and its antiparticle are identical in structure, but their vortices rotate in opposite directions. It is this difference in orientation that explains why one carries a positive charge and the other a negative charge.

Spin

Every fermion possesses an internal rotational motion called spin. This motion does not correspond to a rotation of the particle in space, but to the rotation of the internal vortex that constitutes it. Within this vortex, spations spiral around the center, and the vortex as a whole may itself rotate slightly ahead of or behind the global flow. This internal motion gives rise to intrinsic angular momentum—that is, a rotational property that exists even when the particle is at rest.

Like chirality, spin can take two possible orientations, which are observed experimentally as “spin up” or “spin down.” However, these two orientations do not change the mass or structure of the particle: they simply represent two possible equilibrium states of its internal vortex.

Associated Static Wave

The internal rotation of a fermion, such as an electron, does not remain confined to its center. It leaves a stable imprint in the surrounding spacetime, in the form of a static wave. This is not a propagating wave, but an immobile structure linked to the presence and orientation of the internal vortex. This wave acts as a directional field around the particle: it indicates the direction in which the vortex rotates and thus allows the particle to orient or align itself, for example in a magnetic field. The size of this wave depends on the particle’s velocity. The faster the particle moves, the tighter its internal vortex becomes, and the shorter the accompanying static wave. Conversely, when it moves slowly, the vortex is wider and the static wave more extended. This static wave therefore plays the role of a memory of spin in motion: it accompanies the particle and preserves the orientation of its internal vortex throughout its displacement.

The Neutrino

Not all particles possess the same internal structure. Some, such as the electron, are composed of a closed vortex firmly anchored in spacetime. Others, such as the neutrino, are formed from an open vortex, much lighter. In this model, the neutrino corresponds to the simplest possible form of a vortex: a single swirl, without electric charge. Because it does not interact with electromagnetic fields, it passes through matter almost without effect, which explains why it is so difficult to detect.

The neutrino nevertheless possesses a spin (an internal rotational orientation), but this orientation is always the same: it cannot be inverted by electromagnetic interaction. This distinguishes it from charged particles, whose rotation can be reversed by a field. Its mass is extremely small. This is naturally explained here: an open vortex is far less compact than a closed vortex, and therefore contains much less energy. This geometry leads to a very small mass, consistent with laboratory measurements.

Particle Generations

All particles within the same family (such as the electron, muon, and tau) possess the same internal vortex structure. The difference between them does not come from their form, but from their degree of compactness: how tightly the vortex is wound. When a vortex is weakly compact, the particle is light and stable. When it is more tightly wound, internal density increases, making the particle more massive and less stable. And when the vortex is extremely compact, the particle becomes very heavy and persists only briefly. This is how the model naturally explains the existence of the three generations of particles:

- 1st generation: weakly compact vortex → light, stable, common (e.g., electron, up quark)

- 2nd generation: more compact vortex → heavier, less stable (e.g., muon, charm quark)

- 3rd generation: very compact vortex → very heavy, unstable (e.g., tau, top quark)

This hierarchy does not result from arbitrary properties: it follows directly from the geometry of the internal vortex and the way it interacts with spacetime pressure. In other words, a particle’s mass is not “added” from the outside; it is the consequence of the compactness of its internal vortex.

Dimensional Flavors

Each particle is not defined solely by its mass or charge: it also possesses a dimensional flavor. This term designates the way its internal vortex is organized in spacetime. For example, the electron belongs to flavor 1-2-3 (called the electron flavor): its vortex uses this particular spatial organization. The neutrino, on the other hand, is of flavor 4-5-6 (called the neutrino flavor), in which the vortex is oriented differently. All particles sharing one or more axes with the electron flavor can carry an electric charge. Conversely, those based on the neutrino flavor share no axes with the electron flavor and have no electric charge.

Some particles may partially share the same flavor as the electron. In this case, their charge appears fractional (such as 2/3 or 1/3), which is exactly what is observed for quarks. Thus, electric charge simply follows from the degree of similarity between their internal vortex and that of the electron. In other words, dimensional flavor determines which particles can interact with the electron and which cannot. This notion will play a central role in understanding the fundamental forces, which we will address in the following section.

Further Reading

This popularized presentation is based on a technical corpus formalized in more than 255 documents. To examine the rigorous foundations of the CdR model:

- image030 — Transion threshold — p_max

- image031 — Combinatorial intersection — 6D → 7D transition

- image032 — Compactness hysteresis — 6D topology

- image033 — Opening / closing duality — Three compactness modes

- image034 — Ultra-stable structures — Formation of flavors

- image035 — Super-rotation, chirality, and selector of the four charges

- image037 — Internal dephasing — Quantization of spin S = n/2

- image039 — Inertial mass — Configuration energy of the Φ vortex

- image040 — Three generations — Discrete compactness 1Φ, 2Φ, 3Φ

- image041 — Internal compactness limit — Fermion → global absorption state transition

- image042 — Complete particle table — Φ vortex coherence and emergent masses

These documents detail the geometric derivation of matter particles from the Φ field (pressure thresholds, compactness hysteresis, charges, spin, masses, and generations), as well as the associated numerical simulations and falsifiability criteria.