Fundamental Forces

Gravitation

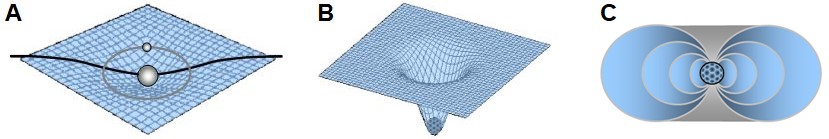

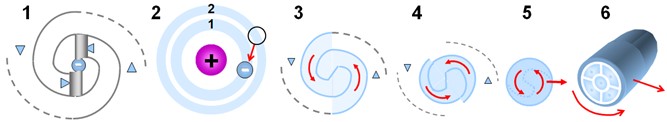

In this model, gravitation does not result from an attractive force, but from local deformations of quantum spacetime caused by the presence of matter. Matter, by transferring spations to another dimension (via transions), partially empties spacetime of its substance. This results in a local depression of density and pressure.

A planet or a photon (figure A) does not experience a force in the classical sense. They follow the curvature induced by the flow of the spacetime fabric. Black holes (figures B and C) would therefore simply be regions where all flavors of spations are transferred out of spacetime. The long-standing question of what happens to matter entering them thus finds an answer: it does not penetrate them; destroyed, it only increases the quantity of spations that can be transferred at once.

Origin of Quantum Forces

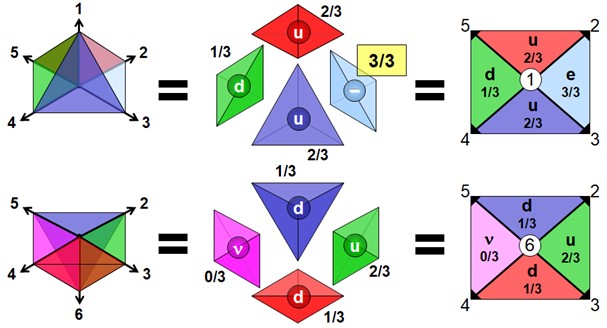

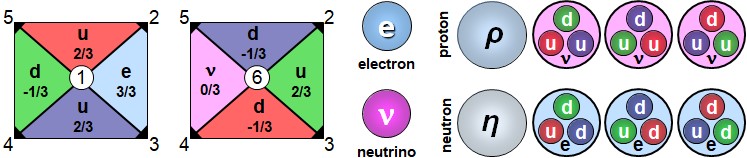

An electron, defined by the three axes (1, 2, 3), is only driven by a flow of spations sharing all three of these axes. A current sharing zero, one, or two axes with it produces no direct interaction. By contrast, a set of particles (such as the three quarks of a proton) can, collectively, cover these three axes and thus drive the electron’s flow. It is this combined overlap of axes that defines electric charge and electrostatic interaction.

Strong Force

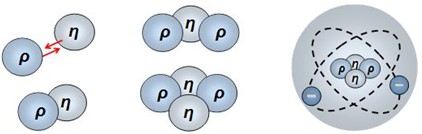

Elementary particles of different charges could associate if they share dimensional axes. As their fields overlap and interfere, they would, by inflareaction, become more massive than the sum of their constituents taken individually.

Immersed in the same field, the force binding them would increase as they move apart, up to the rupture of coupling. This force would therefore display the characteristics of what is known as the strong force. It could indirectly bind nucleons, thus allowing them to form atomic nuclei:

Quark Alternation

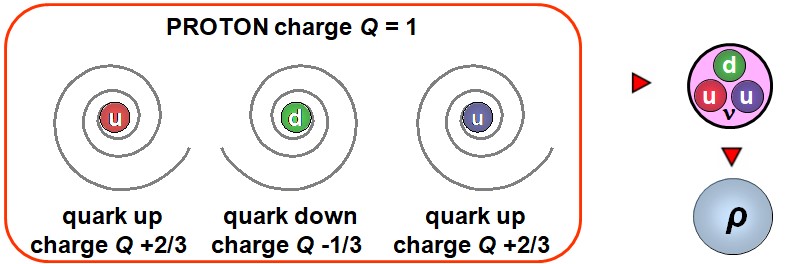

Composite particles, made up of three u and d quarks, thus form the nucleons known as the proton and neutron, which constitute atomic nuclei…

Since quarks, once combined, do not only drive charges linked to the electron or neutrino but also those of other quarks, they alternate in such a way as to prevent any one flavor from accumulating around the nucleon. This alternation maintains internal flux balance and ensures proton–neutron cohesion.

Weak Force

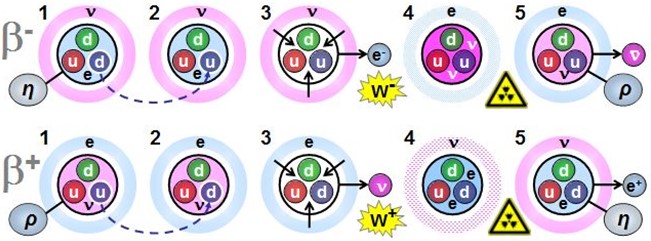

Because a change of quark (from u to d or from d to u) modifies the nucleon’s relationship with electron and neutrino spations, it automatically reorganizes the surrounding flavor layers. This rebalancing releases an electron or positron accompanied by a neutrino, transforming the nucleon into its counterpart: proton into neutron, or neutron into proton.

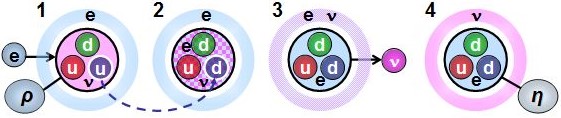

The proton draws the electron charge toward itself without draining it. But if the electron manages to cross its spation layer (3/3), the internal pressure reorganizes: a u quark converts into a d, and the proton becomes a neutron. This rebalancing expels part of the flavor (0/3) as a free neutrino. The electron is not absorbed: it triggers the conversion, after which the new configuration stabilizes as a neutron.

Electrostatic Force

When a set of particles contains an excess of electron-charge spations, spacetime tends to drain this excess and expel the spations associated with other charges. Likewise, an excess of proton charge leads to drainage of that charge and expulsion of electron-charge spations. According to this model, it is this redistribution of spationic flux that gives rise to the electrostatic force.

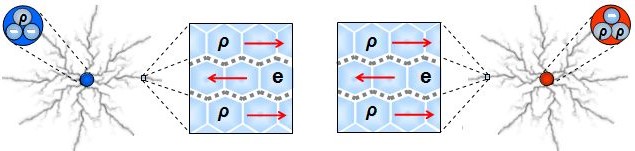

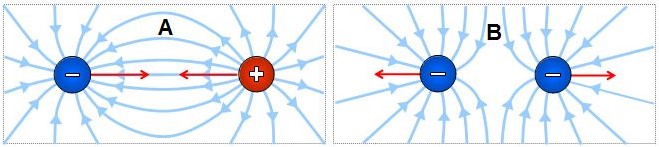

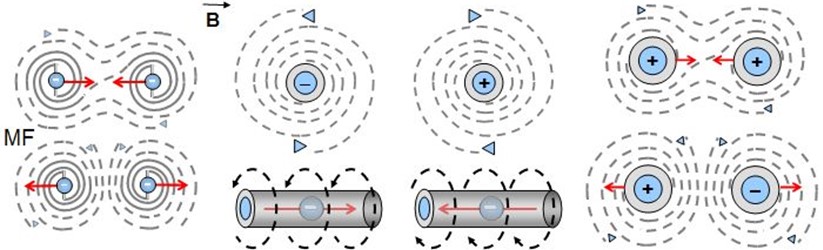

Electrostatic attraction and repulsion arise from the orientation of electron-flavor spations in spacetime. When two regions have complementary deficits, the flux vectors align and connect: attraction occurs. When they share the same deficit, the vectors block one another: repulsion occurs.

Strong and Weak Vector Interactions

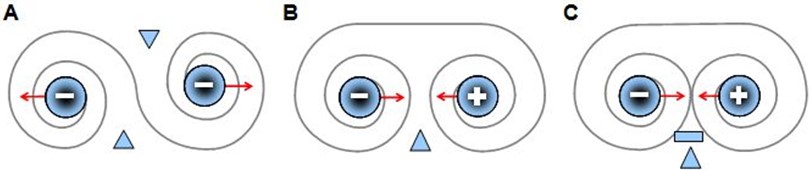

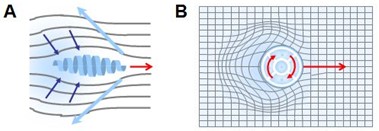

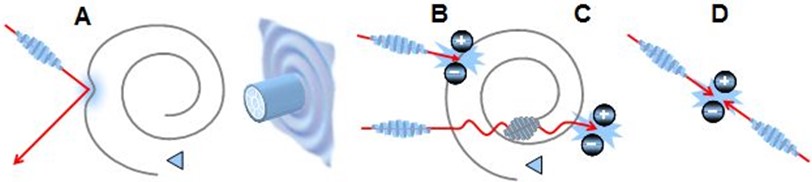

Fields with continuous flow can either repel or bind, depending on how their internal fluxes are oriented. When polarities are identical but unsynchronized, the fluxes interfere and produce repulsion (A). If synchronization is established, they can bind. When polarities are opposite, the fluxes attract (B), but if internal coherence cannot be maintained, the interaction leads to system disintegration (C).

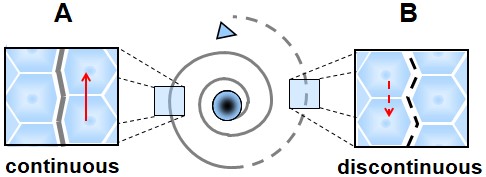

This figure illustrates that spationic field flow depends on distance from the vortex center. Near the core (A), flow is continuous and smooth. Beyond a certain radius (B), flow becomes discontinuous: it proceeds through successive sequences of entrainment and release, like an elastic cord slipping in jerks. This loss of continuity alters how particles can interact over long distances.

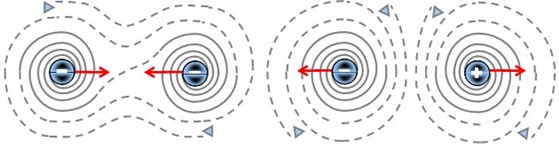

When distance exceeds the radius beyond which flow is no longer continuous, the flux reorganizes into vortices whose orientation determines interaction. Two vortices oriented in the same direction attract, while two vortices with opposite orientation repel. This change of flow regime gives rise to magnetic phenomena.

Magnetic Force

When electrons move through a conductor, their motion creates a vortex in the surrounding field. If two conductors carry electrons in the same direction, their vortices align and combine: pressure between the conductors decreases, causing attraction. Conversely, if electrons flow in opposite directions, the vortices oppose each other: pressure increases, producing repulsion.

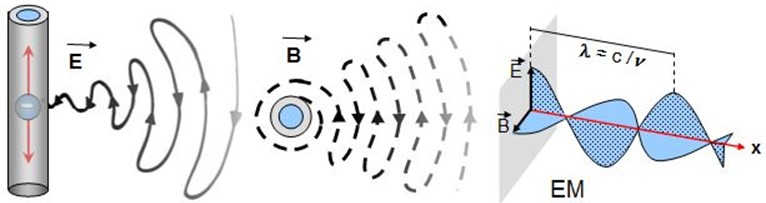

Electromagnetic Waves

A change in flux orientation around a particle creates directional tension in the field (E), which in turn induces a rotation of the flux (B). This alternation between orientation and rotation propagates through space as an electromagnetic wave.

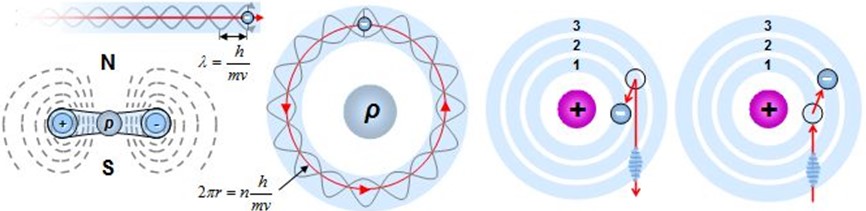

Wave and Orbit

An electron moving around the nucleus generates a wave in the surrounding field. For this motion to be stable, the wave must close upon itself after an integer number of cycles. When this condition is met, the orbit is stable. If not, the electron changes level by absorbing or emitting a photon.

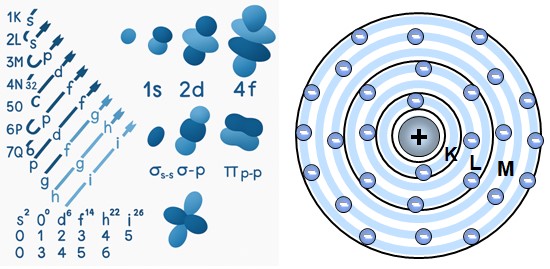

Electrons do not orbit the nucleus like tiny beads, but distribute themselves within stable field forms called orbitals. These forms depend on energy level and motion orientation. The K, L, M… shells group these orbitals by stability, and their superpositions allow the formation of different chemical bonds.

The Photon

The photon is a packet of rotating spations, that is, a small loop of field flux…

When the field changes organization (for example during a change of electronic orbit), it can enter rotation. If this rotation becomes sufficiently strong, the field wave can no longer remain spread out: it closes upon itself, forming a stable vortex, a closed loop of field flow that persists throughout its propagation. The photon is therefore not a solid particle, but a field wave stabilized by its own rotation. This wave carries a coherent phase that propagates at constant speed.

A photon can be understood as a rotating packet of spations. As it advances, it slightly pushes back the field in front of it. But the force that truly propels it comes from behind: spacetime spations rush back to fill the space it has just vacated. This return reaction of the field is inflareaction. It creates overpressure behind the photon, pushing it forward. Its speed is therefore set not by itself, but by the rate at which spacetime can reorganize.

A photon can be deflected, guided, or even transformed depending on the structure of the field it encounters. If it cannot synchronize with local flow, it is simply reflected. In a region where the field is highly compressed, its packet of spations may be forced to unfold into two open vortices, giving rise to a particle and its antiparticle. If the photon crosses a region where field organization is saturated, it may lose internal stability and disassemble. Finally, two photons of opposite phase can neutralize each other and transform into a particle–antiparticle pair.

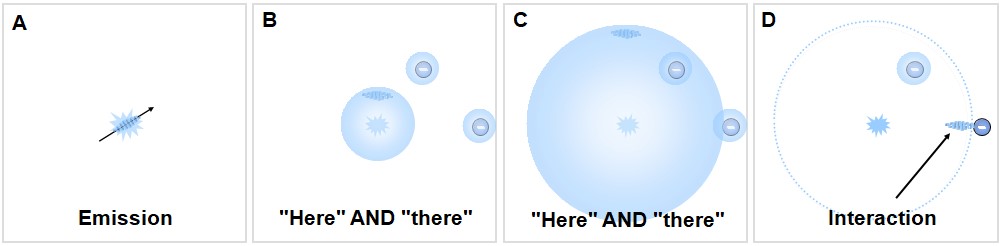

The photon is not a point particle, but the coherent propagation of an orientation of the Φ field. When this propagation remains spread out, it appears as an electromagnetic wave described by Maxwell’s equations. If the variation of orientation reaches a closure threshold, the flux closes into a stable vortex: the quantized photon (QED).

A photon does not possess a precise position in space: it is extended over a coherence volume within which its phase orientation remains correlated. The photon can therefore be “here AND there” as long as coherence is preserved. Interaction occurs only if the encountered electron shares the same local field orientation: phase matching, not spatial proximity, determines the possibility of interaction. If matching fails, the photon is re-emitted (coherent reflection) or transmitted (guided).

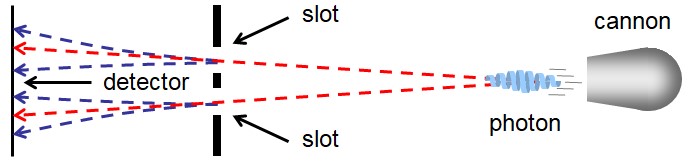

In the double-slit experiment, the photon does not split and pass through both slits as two copies of itself. It possesses an extended coherence volume within which its phase orientation is correlated. What passes through both slits is the phase coherence of the Φ field, not the particle itself. The interference pattern appears as long as this coherence is preserved; if the path is measured, the local field orientation is constrained and coherence contracts, causing interference to disappear.

Further Reading

This popular presentation is based on the technical documents of the 043–065 series, which develop in detail the geometric origin of forces, spationic interactions, photon structure, and electromagnetic phenomena in the CdR model.

- image043 — CdR gravity

- image044 — Pressure, energy, Φ flux

- image045 — Electrostatic attraction

- image046 — Charge distribution

- image047 — Nucleon structure

- image048 — Internal spationic states (0/3)

- image049 — β⁻ decay

- image050 — Electron capture

- image051 — Θ EM geometry

- image052 — Electrostatics: continuous flow

- image053 — Directional interactions

- image054 — Continuous vs discontinuous regimes

- image055 — Magnetism: transverse effect

- image056 — Interaction between currents

- image057 — Classical EM wave

- image058 — Orbital quantization

- image059 — 2Φ modes and photon

- image060 — CdR photon

- image061 — Refraction / photonic guiding

- image062 — Light–matter interaction

- image063 — Perturbation → wave → photon

- image064 — Coherent range Z_coh

- image065 — Double slit (CdR path)

These documents present the internal mechanisms of the CdR model: spationic coupling, emergence of forces, photon dynamics, orbital stability, long-distance decorrelation, and possible experimental signatures.