Spacetime

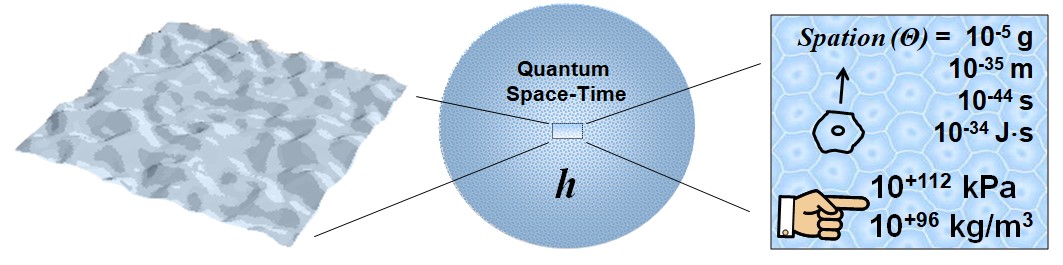

The six-dimensional hyper-volume (6D) would correspond to a cosmic domain: it is from it that what we call spacetime would arise. But this spacetime would not be a continuum, as classical physics still assumes, but a quantum structure, made of discrete cells. These cells—designated by the name spations—would constitute the elementary unit of spacetime. Each of them would represent a quantum of space, time, mass, and energy—in other words, an elementary unit of spacetime.

A spation is not a particle, but a structural cell, a fundamental unit. All its characteristic quantities—size, duration, density, pressure, energy—emerge directly from the immanence constraint , applied at the level where internal coherence reaches its saturation threshold. Its average size is on the order of 10⁻³⁵ meters, its traversal time by a wave on the order of 10⁻⁴⁴ seconds, its mass on the order of 10⁻⁵ grams, and its elementary energy on the order of 2×10⁹ joules, corresponding to Planck energy—the threshold at which quantum and gravitational effects merge. These are the values that define the limit below which our classical concepts of time, space, mass, or energy cease to have isolated meaning.

Spations would be in perpetual agitation, compressed against one another in extreme density, mutually exerting a pressure of about 4.63×10¹¹⁰ kPa (i.e. 4.63×10¹¹³ Pa), a value corresponding to Planck pressure, the limit at which density and energy become inseparable. Likewise, their mass density would reach values on the order of 10⁹⁶ kg/m³, making the very concept of “vacuum” highly relative: what is commonly called “the vacuum of space” would in reality be empty only of ordinary matter, but not of real substance. This “relative vacuum,” saturated yet compensated, is at the origin of the cosmological constant, interpreted here as the macroscopic signature of fluctuations in the spationic medium.

Now, if one accepts that energy is quantized, then Einstein’s equation implies that mass is also quantized: the existence of an energy quantum implies that of a mass quantum, and therefore of a spacetime quantum. This means that matter cannot be divided indefinitely: beyond a certain threshold, one no longer obtains particles, but spations. And it is these, according to this model, that constitute the substrate of everything that exists.

But before addressing matter itself, it is essential to explore certain specific properties of spacetime, or at least some functional ways of representing it—in order to better understand how matter, energy, and the fundamental forces can emerge from it.

Dynamic viscosity of spacetime

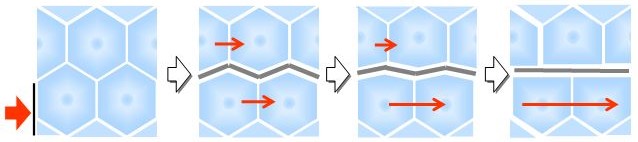

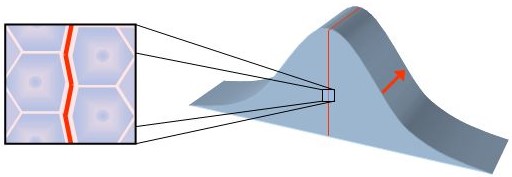

The cellular medium constituted by spations would not be rigid, but endowed with a dynamic viscosity. This means that spacetime cells can slide relative to one another, but not without interaction: any local motion in the medium produces an effect of jostling, transmission, or resistance to motion.

Concretely, when a set of spations is set in motion, it drags its neighbors along. This displacement encounters a form of internal resistance, a viscosity, similar to that of a very dense fluid. However, this behavior is not linear: as long as the differential velocity between two zones of the medium remains below a certain threshold, viscosity is stronger. Beyond this threshold, sliding becomes freer, almost without resistance.

As a result, it is not only mass or energy that opposes inertia to a change of state, but spacetime itself, as a dynamic substrate. This property is crucial: it makes possible the transmission of an impulse, the propagation of a wave, the conservation of motion—in short, mechanics as we know it.

Without this viscosity, no memory of motion, no inertia, no delayed interaction would be possible. In other words: inertia is not a property of matter, but a property of the spationic medium.

And as with the previous quantities, the characteristic values of this viscosity are not borrowed from existing physics: they are deduced directly from the structure of the spations themselves. For details (formalism and calculations), click on the image above.

Sub-spatial interactions

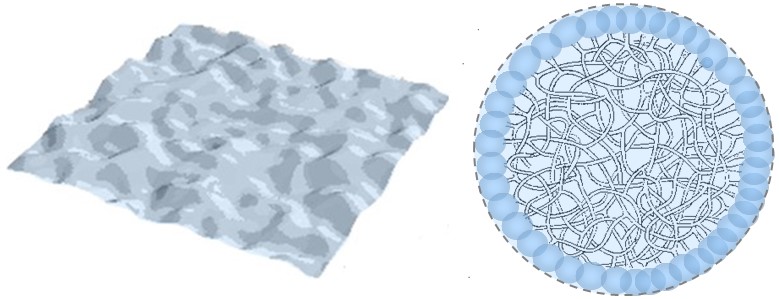

The enormous energy fluctuations observed in the quantum vacuum cannot be explained solely by local interactions between spations, like those of a heated gas enclosed in a container. One must consider deeper, more fundamental interactions, which could be described as sub-spatial, because they precede and exceed the simple geometric structure of spacetime.

Each spation, let us recall, is not an isolated object, but a three-dimensional interface of a six-dimensional being. Its state—its form, size, apparent mass, presence—is therefore not fixed, but fluctuating, entangled with those of countless other spations in the universe. This means that a pressure exerted locally on one spation could be instantaneously reflected elsewhere, on other spations, even very distant ones.

These sub-spatial interactions would form a hidden, non-local fabric, responsible for exchanges of energy and information no longer respecting the classical limits of propagation in space or time. It is this deep entanglement between spations that would be at the origin of quantum bubbling: a state of perpetual fluctuation, where presence and absence, expansion and contraction, emergence and disappearance follow one another at a scale that escapes our usual representations.

In other words, the quantum vacuum would not be empty, but an ultra-connected foam of existence, in perpetual effervescence, where every event, however minute, affects the whole.

For the detailed diagram and associated formalism, click on the image above.

Inflareaction

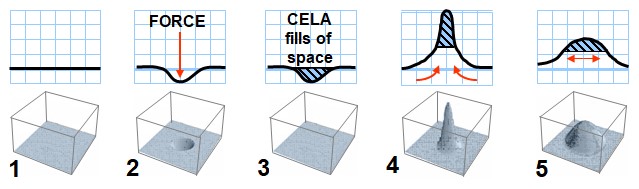

In a liquid, when a force is exerted on a volume, the displaced fluid particles continue to move for a moment after the impulse, carried by their own inertia. This is a well-known dynamic. But if spacetime is constituted of spations, and these are made of CELA, the dynamics are no longer the same.

When a force is exerted in spacetime, it locally contracts the spations. But unlike a classical fluid, this does not leave a void. The substance of the Real, CELA, by its very nature, immediately fills any reduction of density. This results in a borrowing of density from the rest of the universe. This momentarily increases pressure and density in that zone.

But this reaction is not purely passive. The resulting excess rebounds, exerts a reverse push, and drives a self-reinforcing dynamic. This contraction–expansion loop, endowed with an amplifying rebound effect, is called inflaréaction.

This phenomenon accounts for the way a local perturbation can transform into an energetically coherent phenomenon, capable of self-organization and eventual persistence: such as a particle, a wave, or a quantum of interaction.

Inflareaction thus constitutes a fundamental mechanism for the generation of form, energy, memory, and identity in spacetime. It could play a central role in the appearance of particles, forces, and more broadly in the quantum dynamics of the universe.

Further Reading

The illustrations on this page are based on detailed technical documents from the Spacetime series. To examine the rigorous foundations of the CdR model:

- image023 — Θ scales, fundamental constants, and emergence of c and ℏ

- image025 — Dynamic viscosity of the Θ medium — Non-Newtonian regime and shear

- image027 — Sub-spatial interactions — Non-local coherence of the Θ network

- image028 — Inflareaction — Local overpressure and coherent rebound

- image029 — Stabilized overpressure — Stationary modes of the Θ field (closed inflareaction)

These documents include mathematical formalisms, falsifiability criteria, and detailed correspondences between internal geometry and quantum phenomena.